The Romantic Period of Music

Ask most people what they consider a romantic song, and you'll get answers like John Legend's "All of Me" or just about anything by Marvin Gaye. But as you know, the capital "R" in Romantic music refers to works composed in the Romantic style, which arose during the Romantic Period. So, what characterizes Romantic Period music? How did it evolve? These are some of the questions we'll explore here.

What Is Romantic Era Music?

At its core, composers of the Romantic Era saw music as a vehicle for individual and emotional expression. They considered it the art form most capable of conveying the full spectrum of human emotion. As a result, Romantic composers broadened the emotional scope of their music and often used narrative forms to tell distinct stories.

They prioritized emotional and narrative content above strict formal structure, breaking many of the Classical Period's rules. However, they didn’t reject Classical forms outright—instead, they used them as a foundation, feeling free to bend or expand them as needed.

Beethoven is often seen as the originator of this approach. Living and working during the transition from the Classical to the Romantic Period, he inspired generations of Romantic composers. His symphonies redefined the form and introduced features characteristic of Romanticism, such as autobiographical themes and named movements—like the third movement of his String Quartet No. 15 in A minor, Op. 132: "Song of Thanksgiving to the Deity from a Convalescent in the Lydian Mode."

Ultimately, Romantic composers evolved and expanded the Classical structure into a more complex, expressive musical language.

Origins and Context of the Romantic Period

Music joined the Romantic movement slightly later than literature and visual art. Historians debate the period’s start and end dates—some place it squarely in the 19th century, while others trace its beginnings to the late 18th century. In literature, William Blake's Songs of Innocence (1789) and Samuel Coleridge’s Kubla Khan (1797) are seen as early Romantic works. The movement reached its peak in the mid-1800s, permeating all art forms and popular thought.

Romanticism’s emphasis on individual expression stemmed from the Enlightenment's focus on individualism, though the Romantics rejected the Enlightenment’s prioritization of logic and rationality. They also reacted against the Industrial Revolution’s values of mechanization, mass production, and urbanization, which they saw as dehumanizing and contrary to an idealized natural state.

The Romantic Era was also shaped by political and nationalistic tensions, with revolutions and wars sweeping across Europe—from the French Revolution (1789) to the mid-century revolutions and national unifications of the 1870s. This historical backdrop deeply influenced Romantic music, just as it did visual art and literature.

Four Artistic Inspirations in Romantic Music

Given the context, it’s easy to see why Romantic composers gravitated toward four recurring artistic themes (in the broad sense of the word "theme"):

- Extreme emotional states—Whether autobiographical or based on literary characters or imagined experiences, composers aimed to portray the breadth of human feeling.

- Nature—Especially its untamed aspects, such as storms or mysterious forests, often depicted through evocative musical techniques.

- The supernatural—A fascination born partly from the uncertainty of rapid scientific advancement.

- National identity—Using folk music and stories to express patriotism or reclaim cultural traditions.

These themes often overlap within a single piece. Romantic composers frequently turned to literature for inspiration, using narrative and emotional frameworks to craft music with deeper meaning.

Mendelssohn's scherzo from A Midsummer Night's Dream

Rise of the Musical Virtuoso

Another crucial aspect of Romantic music wasn’t thematic but personal: the rise of the composer-performer as artiste and virtuoso. Composers like Paganini, Liszt, and Brahms were not just writers of music but celebrated performers with extraordinary technical skill.

This development was both artistic and practical. Romanticism celebrated self-expression, and musicians sought distinctive personal styles—what we might call "branding" today. Moreover, with the decline of the noble patronage system, composers were no longer dependent on aristocratic approval. The rise of a middle class with time and money to attend concerts allowed composers to reach broader audiences—and make a living.

But this also introduced a tension that remains today: Should the artist prioritize personal expression or audience expectations? This era also saw the rise of the music critic, like E.T.A. Hoffmann, who helped audiences interpret and evaluate this increasingly complex music.

How Romantic Music Differed from Classical Music

Romantic music didn’t break completely with Classical tradition—it expanded its vocabulary. For example, Schubert’s Unfinished Symphony defies traditional phrasing structures, and Mahler’s Symphony No. 2 explores distant keys without restraint.

Romantic composers also embraced and developed new techniques to express a broader emotional range:

- Chromatic harmonies with semitones and unconventional progressions.

- Leitmotif—themes associated with characters or emotions, pioneered by Wagner.

- Unending melody—allowing melodic lines to continue without traditional cadences.

- Rubato—flexible tempo reflecting emotional shifts.

- Faster tempos and complex rhythms demanding virtuosity.

- Special techniques like sul ponticello and sul tasto to expand tonal palette.

These expressive tools were supported by instrumental innovations.

Changes in Instruments and the Orchestra

The piano underwent significant transformation: expanding from five to eight octaves, adopting metal frames, and gaining stronger strings. These changes enriched its tone and dynamic range.

Woodwinds and brass also improved, with better materials and new inventions—like valves for brass instruments and the creation of the Wagner tuba. New instruments and better construction meant richer sound.

However, one of the most striking changes was the size and makeup of the orchestra itself. Romantic composers demanded larger orchestras for their increasingly dramatic works. Mahler’s Symphony No. 8, for instance, calls for two choirs and 120 musicians. While Classical orchestras had around 30 players, the Romantic orchestra began to resemble the one we know today.

This larger ensemble allowed for broader dynamics, richer harmonies, and more tonal color. It also permitted unconventional instrumentation—such as the cannons in Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture.

Changes in Musical Forms

Romantic composers reimagined formal structures. The symphony grew more expansive and complex, but composers also created "miniature" works:

- Etudes—short works for skill development, like Paganini’s 24 Caprices or Chopin’s piano etudes.

- Preludes and overtures—once introductions, now standalone pieces (e.g., Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet).

- Impromptus—pieces that sounded improvised, usually for solo piano.

- Folk-inspired forms—such as the German lied, Polish polonaise and mazurka, and the Viennese waltz.

One especially important innovation was program music.

Rise and Scope of Program Music

Program music tells a specific story or paints a vivid scene. Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique narrates his obsessive love for an actress, with five movements titled:

- Passions

- A Ball

- Scene in the Fields

- March to the Scaffold

- Dream of a Night of the Sabbath

Sometimes program music was based on mythology or literature. Dvořák’s The Golden Spinning Wheel retells a Czech folk tale. Tone poems like these could be narrative or simply evocative, transporting listeners to a time or place.

Nationalism in Romantic Music

Sibelius’s Finlandia is a clear example of nationalist music. While not all works were overtly patriotic, many Romantic composers drew on folk traditions for inspiration. In the Classical Era, that might have seemed provincial, but Romanticism welcomed such expressions.

Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsodies use Hungarian folk styles. Brahms, though German, was inspired by Hungarian-Jewish musicians. Dvořák's New World Symphony sought to define an American musical identity based on folk sources.

The related idea of exoticism involved drawing on foreign lands for inspiration. Verdi’s Aida (set in Egypt) and Puccini’s Turandot (set in China) reflect this trend.

Romanticism Evolves: Toward Post-Romanticism

As Romanticism emphasized personal expression and rule-breaking, it naturally evolved. By the late 19th century, composers began abstracting emotional content—ushering in musical Impressionism. Some returned to Classical structures but infused them with Romantic themes of mysticism and the grotesque.

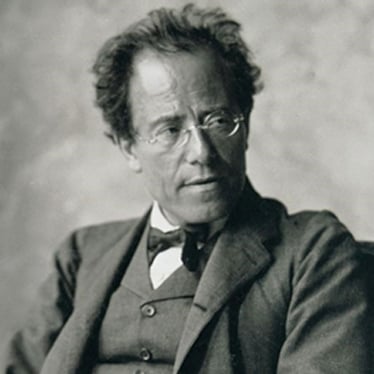

Mahler stands as a bridge between Romanticism and Post-Romanticism. Eventually, the Romantic ethos of innovation and boundary-pushing gave way to Modernism and Postmodernism—culminating in figures like John Cage, who rejected traditional aesthetics altogether.

Romantic music remains beloved for its drama, emotion, and storytelling. Its enduring popularity speaks to its power to move, provoke, and inspire across generations.

Exploring Romantic Composers and Their Works

We've covered a number of Romantic Era composers and some of their works. As an artistic epoch spanning anywhere from 80 years to slightly over a century, it spawned a huge volume of amazing composers and music. We named our Spotify list of Romantic Era music "20 Hours of the Best Music from the Romantic Era," and it covers a lot! You'll see we broke it up by form, from symphonies to tone poems through concertos and string ensembles and closing off with the operas and ballets.

If you prefer to start with the "must-know" list of Romantic Era composers, then check out this list of ten of the most influential. You'll find some composers already discussed, plus a few others. For each composer, we've also linked one extraordinary performance of one their most important works.

Above Images: Gustav Mahler, courtesy of wikicommons, and Edvard Grieg, De Agostini/A. Dagli Orti/Getty Images.